A Mary’s Musings post months in the making!

You may have seen on my Mary’s Musings Instagram I visited Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in March. This temporary exhibit dispersed reconstructions of Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture throughout the Met’s European sculpture galleries.

Visitors to the exhibition could study marbles and bronzes that no longer retained their ancient polychromy alongside scientific reproductions that illustrate the vibrant and rich color palette used in the original crafting of these works. Inside the picturesque Leon Levy and Shelby White Court at the Met, dozens of classical sculptures, busts, and reliefs are precariously placed around the central fountain. The vast majority of these works no longer retain their original colors.

Art History students learn in survey courses that these sculptures used to be painted, but this point is hard to conceptualize. To this point, I cannot recall a single colorful reproduction featured throughout the various texts I flipped through. Chroma exhibited the marble and plaster reconstructions of German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann. These works force the viewer to grapple with an unfamiliar view of classical sculpture, which contradicts the customary plain white marble in favor of a bold and dramatic visual culture.

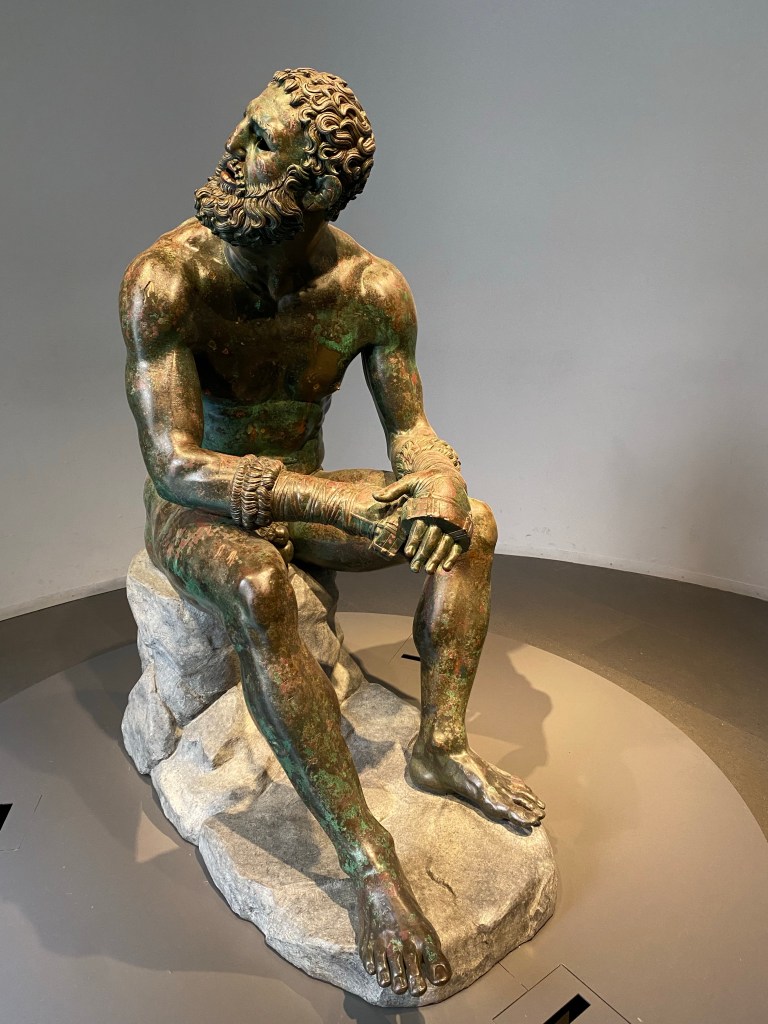

The life-size The Boxer at Rest (c. 330 – 50 BC) and Hellenistic Prince (c. 2nd century BC) in Chroma left a lasting impression on me. The pair share an interesting history, that stems from their rediscovery in 1885 at the remains of the Baths of Constantine. A few months later, I was fortunate to view the original bronzes alongside one another in Rome’s Palazzo Massimo alle Terme. The survival of these two works is a remarkable feat as many bronzes from this period were often melted down and repurposed.

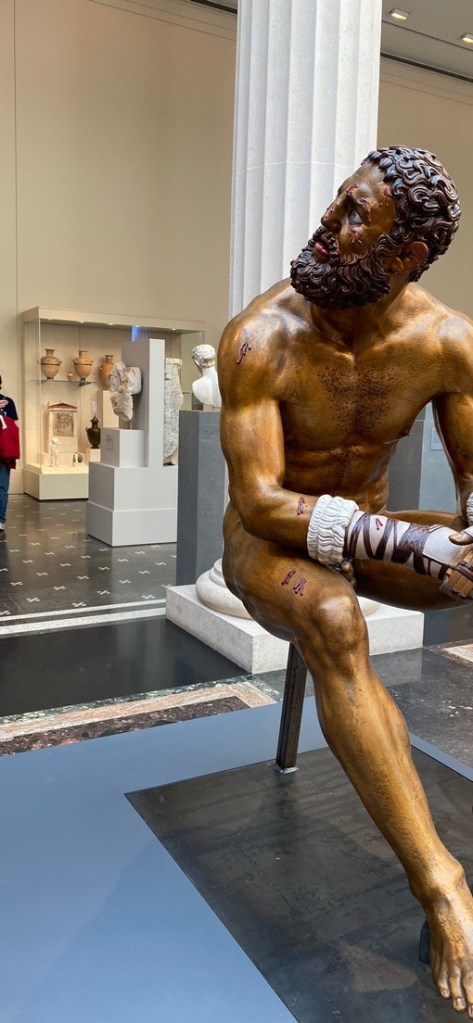

The Boxer at Rest is renowned example of a Hellenistic Greek original bronze. It portrays a fighter pausing briefly after a match. He still wears his Ancient Greek boxing gloves, which are strips of leather attached to a ring fashioned around the knuckles. The sculpture would have brandished inset eyes (visible on the reproduction at Chroma). Gashes and droplets of blood (originally inlaid with copper) cover the bruised and battered bronze body. These wounds are more apparent in the Chroma version as the viewer can more readily pick out the shimmering and cuts and marks.

#FunFact The Boxer at Rest visited the Met in 2013, as an extension of the Year of Italian Culture in the United States.

While the work is a remarkable example of the lost-wax process in its own right, it was compelling to see both the original and polychrome reconstruction in person and place both works in a comparative conversation. As my knowledge of the art historical canon continuously expands, I could grasp a discernable visual connection with the Boxer’s stance and Goya’s (1746-1828) Giant (1818), which I viewed in person also at the Met last year. Although Goya did not live to see the rediscovery of the bronze, the posture, composition of the figures, and inherent bulkiness between the two works share many similarities that manifest themselves in other art historical forms.

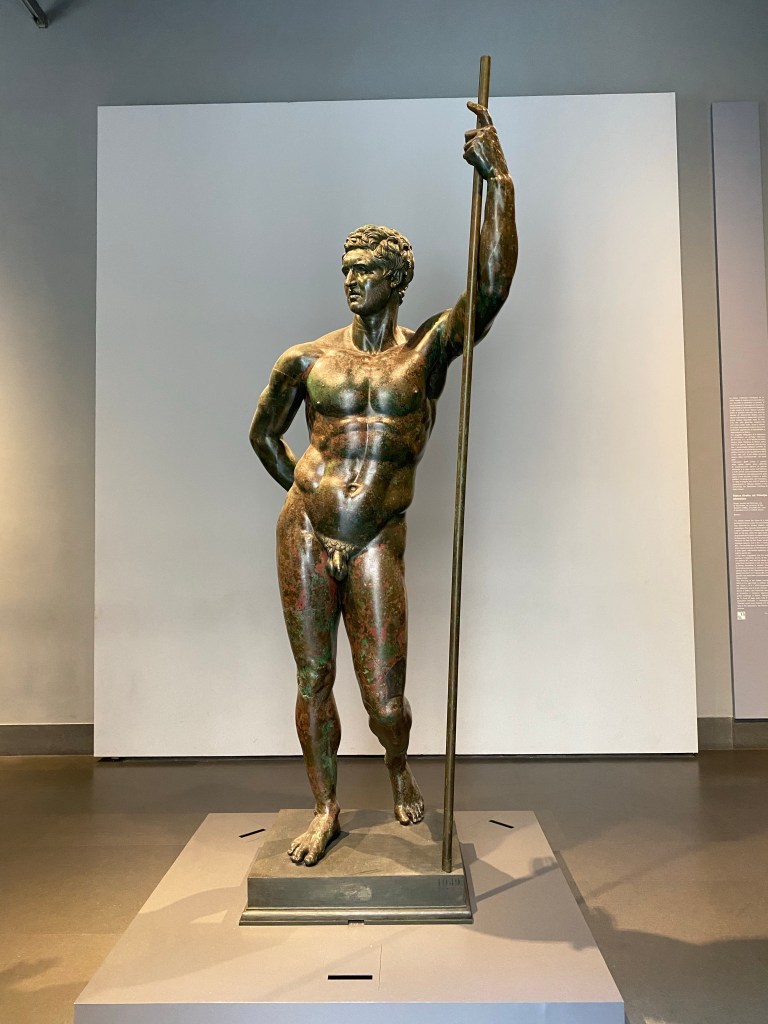

The Hellenistic Prince is the second work archaeologists found with The Boxer. Scholars believe the figure is supposed to be either a Prince or a Roman General (consensus has favored Scipio Aemilianus). However, the namesake has traditionally been associated with the piece (It is important to note that the two works were not originally intended to be displayed together, because their years of creation differ). The Prince crafted to have an idealized body leans on a spear (which is now lost).

Both works inform our understanding of Greek bronzes and viewed in conversation with their polychrome reconstructions, enhance our understanding of their intended reception.

Categories: Uncategorized