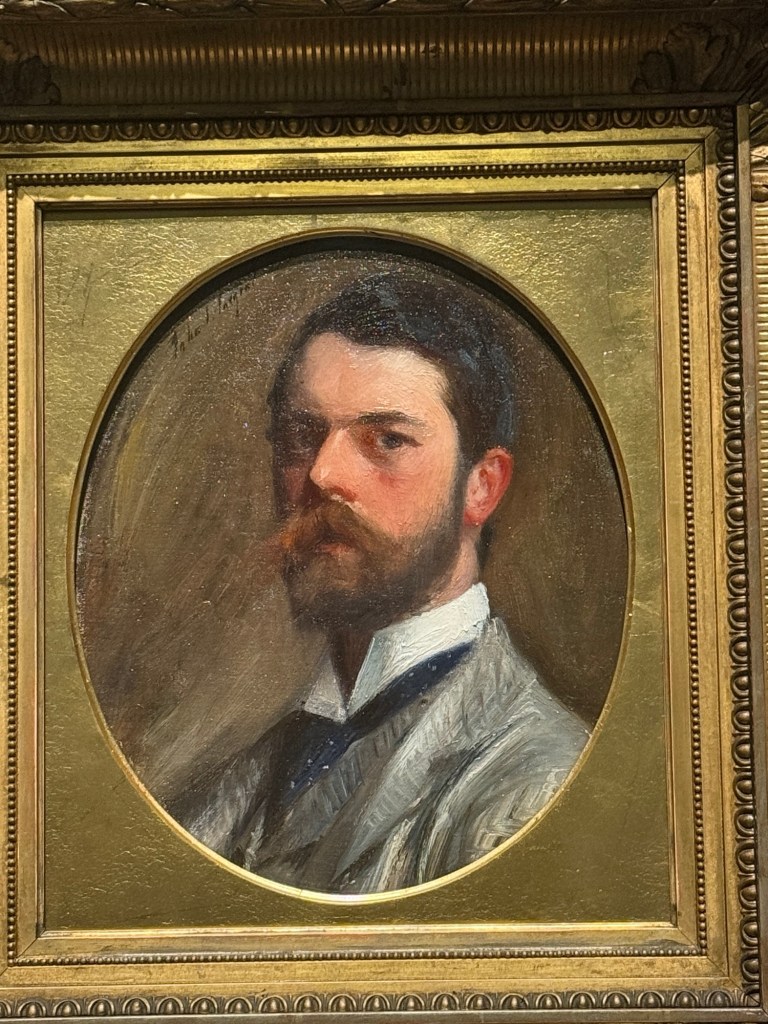

John Singer Sargent’s (1856-1925) reputation blossomed from the roots he planted in Paris in the late-nineteenth century. Sargent and Paris explores the artist’s time in the city and chronicles his rise to an international sensation through the curation of the galleries presented at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sargent moved to Paris in 1874. While widely heralded as an American artist, John Singer Sargent was born in Europe to American parents. His prime placement in Europe enabled Sargent to not only explore a vast variety of countries but also immerse himself in multiple languages and cultures. Upon arrival, Sargent studied with French portraitist Carolus-Duran (1837-1917) and enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts.

This exhibition excels in its intimate, yet comprehensive narratives which come alive in sections of the galleries. A central thematic idea grounds the overarching tone of a given hang, but also chronologically walks the visitor through a specific period in Sargent’s life. A wall of text greets the visitor and categorizes the curation of paintings in a given room. In the initial gallery, it displays Sargent’s skills and technical prowess upon his arrival in the city, which in turn sets the stage for his gradual artistic growth over the decade he lived and painted in Paris and the surrounding areas. This growth comes alive through the visitor’s progression through each room.

Aside from visiting the exhibition eight times, I attended a captivating lecture on the exhibition at the American Art Fair led by Stephanie L. Herdrich, finally found an excuse to finish Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X as well as flip through articles surrounding the namesake’s cameo in the Gilded Age. To say this was the “Summer of Sargent” was an understatement. Although I viewed Fashioned by Sargent at the MFA in 2023, this exhibition, instead of focusing on a centralized theme as the bedrock for the exhibition, branches out to chronologically and illustratively showcase the ascendancy of arguably the greatest portrait painter of the period.

Sargent’s sensational canvases are on display throughout the exhibition through a wide variety of loans from a myriad of public and private collections. Arguably one of the most anticipated loans is The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), a work that very rarely leaves the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It is one of two paintings flanked in a long, rectangular gallery that places this work in conversation with Sargent’s study of Velázquez’s Las Meninas. The empty space beckons close looking and elicits the eye to hone in on visual similarities between the two works. The young girls, the empty space on the canvas, and the dark, somber palette are in conversation with one another and show Sargent’s inspiration and close analysis of the piece.

The galleries analyze Sargent’s time in Paris from virtually every plausible angle. As previously mentioned, the initial arrival of Sargent is introduced by his formal educational training and is transitioned into his excursions outside of his studio – illustrated by paintings documenting his travels to Italy and the French countryside as well as Spain and Morocco. Additionally the exhibition also boasts a wide variety of well and lesser known portrait commissions and gifts Sargent completed during his tenure in Paris.

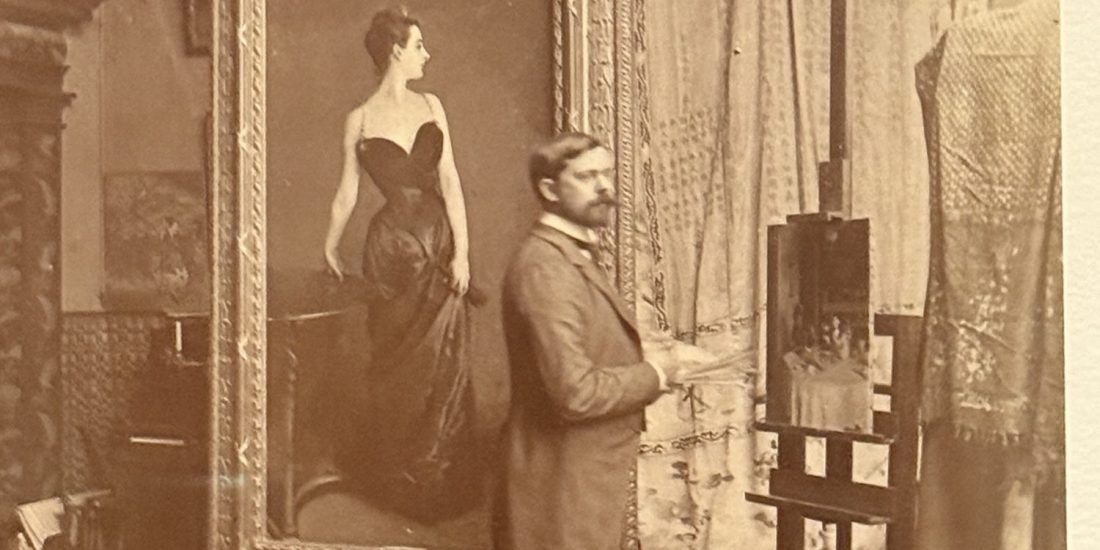

Madame X (1883-1994) is the face of Sargent & Paris. A detailed shot of her scandalous strap graces the massive banner flapping over 5th Avenue, the cover of the exhibition catalog, as well as the bars of chocolate and fresh new MET Tote bags in the exhibition’s gift shop. It’s only right that an entire gallery be dedicated to Sargent’s artist conception and production of the portrait of Virginie Avegno Gautreau (1859–1915), which the artist claimed was “…the best thing I have done.” Dozens of preliminary sketches from public and private collections flank the walls aside the grandiose placement of the final canvas. It is widely believed that the sheer number of preliminary sketches Sargent executed of Gautreau surpasses any other work he completed for a portrait.

I personally enjoyed the unfinished canvas study of Madame X on loan from the Tate. I stood in front of it for several minutes in the galleries and kept twirling my neck back and forth to look at the final version – noting how the brushwork in the final is obviously more defined but also see color variations in the skin tone and hues of the infamous black gown. I’ve visited Madame X on many trips to the Met, but it was a real treat to see her in conversation, a glance away, from all of these works which ultimately led to her final canvas and its unveiling at the 1884 Paris Salon.

The final galleries discuss the aftermath of the slipping strap heard round the world, the repainting of the strap by Sargent, and ultimately the perseverance of his reputation in Paris and beyond. He remains to be heralded as one of the masters of portraiture, and this exhibition painstakingly chronicles his time in Paris where this reputation soared following the 1884 Paris Salon.

For me, this was truly the Summer of Sargent, and I’m grateful I had the opportunity to view this exhibition on several occasions before it heads to Paris for Mr. Sargent’s reintroduction to the Parisian art scene.

Categories: #marysmusings, #museum, arthistory